Python is a fantastic language! At least, in my opinion it is. There is a great ecosystem of libraries that you can use and I find it a very satisfying language to work with. But being the interpreted language that it is, Python is not the fastest. To speed things up, you could turn to C or C++. Extensions will allow you to use functions and programs written in those languages. This offers faster execution speed, and you will not be troubled by the GIL.

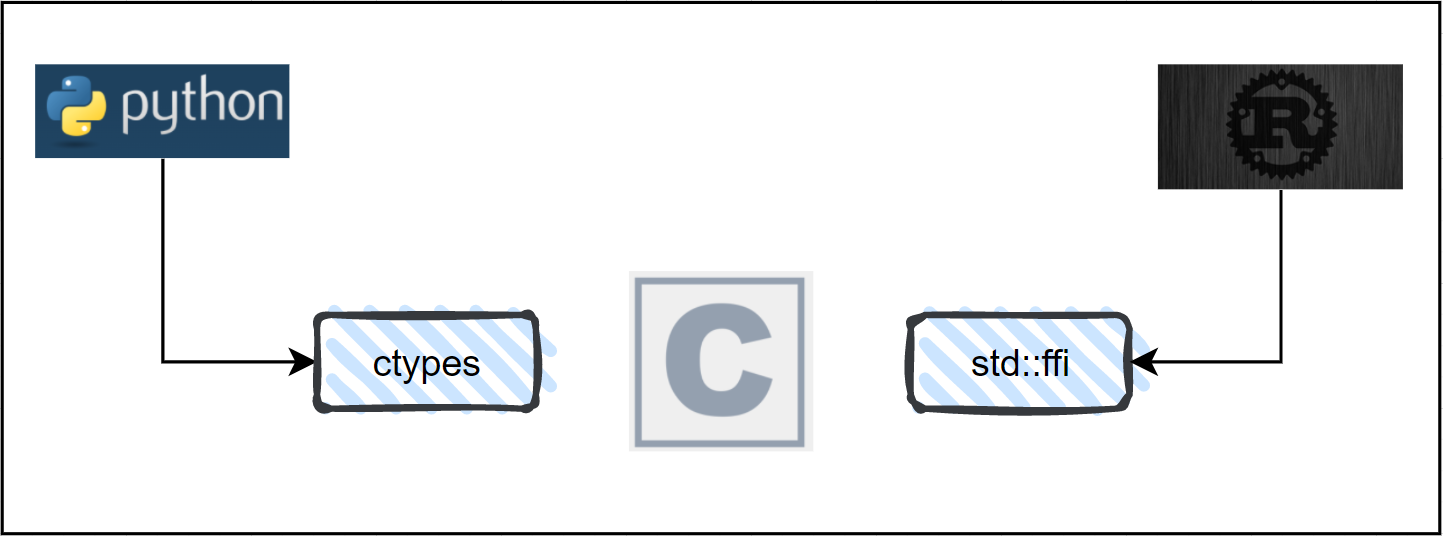

In addition to using C or C++, another thing to consider is Rust. Rust offers an FFI (Foreign Function Interface), which allows you to export Rust functions to C. By having Python make use of these exported C functions, you can glue the Python and the Rust universe together. This way, you can bring in some Rust precisely where you need some additional power.

In this article, I will cover a few basic examples on how to call several Rust functions from Python. On the Rust side, I will use the ffi from the std and on the Python side, I will stick to ctypes:

Calling a Rust function from Python to print a string.

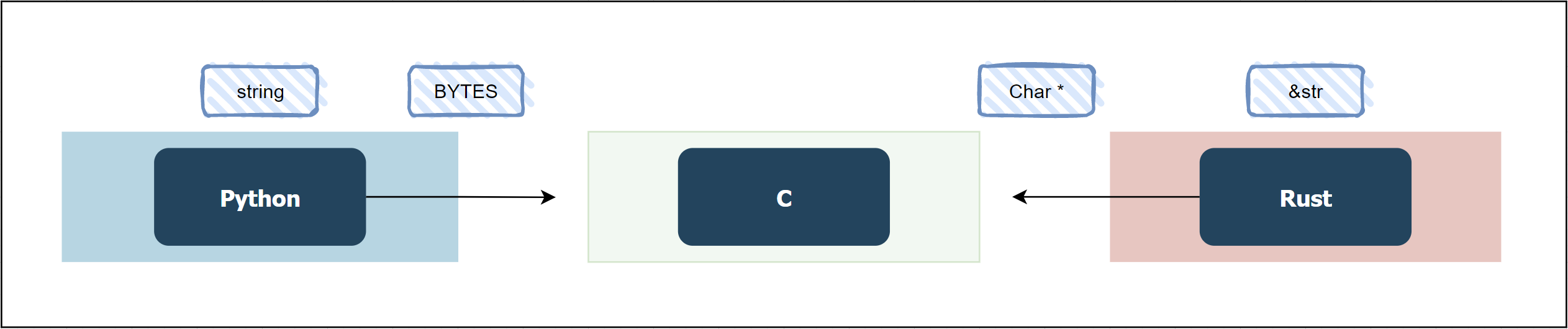

To start thing of, we will write a Rust function that prints a string. The following illustrated what will happen:

On the Python side, we will do the following:

- import the library file that contains the function that Rust exported to C

- convert a string to bytes

- call the function that was exported from Rust

- the argument to the Rust function on the Python side are the UTF-8 encoded bytes

On the Rust side, we will do the following:

- create a new library

- specify we are building a dynamic Rust library in the

Cargo.tomlfile - write the Foreign Function Interface in Rust that is compatible with C

- read the Python input, coming in via C, as a

Char *. - build the Rust library

After this, we run the code!

The Python side.

import ctypes

rust = ctypes.CDLL("target/release/librust_lib.so")

if __name__ == "__main__":

SOME_BYTES = "Python says hi inside Rust!".encode("utf-8")

rust.print_string(SOME_BYTES)

First, we import ctypes. After that, we specify where we can find the .so file. The python script, called print_string.py, will be placed in the folder where I am building the rust library. After I run cargo build --release, this will be the layout of the files involved:

rust_lib/ ├── target/ | ├── lib.rs ├── target/ │ ├── release/ │ ├── librust_lib.so ├── print_string.py

In the main section of the Python, I start by converting a string to bytes by calling .encode("utf-8") on the string. This will output the string in UTF-8 encoded bytes. After this, I call Rust function using rust.print_string(SOME_BYTES). The first part is a reference to the library that we loaded earlier. The second part, print_string, is the name of the exported Rust function. And SOME_BYTES is passed as the argument to the function we are calling.

We can also provide the argument to the Rust function in an alternative way. Let’s add the following to the print_string_script.py:

rust.print_string(

ctypes.c_char_p("Another way of sending strings to Rust via C.".encode("utf-8"))

)

In this case, we use ctypes.c_char_p to pass the value into the rust function. c_char_p is a pointer to a string.

The Rust side.

On the Rust side, we start off creating a new library using cargo new --lib. After this, we edit the Cargo.toml file:

[package] name = "rust_from_python" version = "0.1.0" authors = ["Said van de Klundert"] [lib] name = "rust_lib" crate-type = ["dylib"]

This indicates we are building a dynamic Rust library and we will be using libc.

Then, we write the lib.rs file:

use std::ffi::CStr;

use std::os::raw::c_char;

use std::str;

/// Turn a C-string into a string slice and print to console:

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn print_string(c_string_ptr: *const c_char) {

let bytes = unsafe { CStr::from_ptr(c_string_ptr).to_bytes() };

let str_slice = str::from_utf8(bytes).unwrap();

println!("{}", str_slice);

}

The first line brings the CStr into scope. This is a struct that represents a borrowed C string. The documentation says the following:

This type represents a borrowed reference to a nul-terminated array of bytes. It can be constructed safely from a &[u8] slice, or unsafely from a raw *const c_char. It can then be converted to a Rust &str by performing UTF-8 validation, or into an owned CString.

We will use it in this way and convert the CStr to a Rust &str.

The second line, use std::os::raw::c_char;, brings the c_char type into scope.

After this, we bring use std::str; into scope so that we have access to from_utf8 later on. This will allow us to convert bytes to a Rust &str.

Now, let’s focus on the function:

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn print_string(c_string_ptr: *const c_char) {

let bytes = unsafe { CStr::from_ptr(c_string_ptr).to_bytes() };

let str_slice = str::from_utf8(bytes).unwrap();

println!("{}", str_slice);

}

The extern keywork facilitates the creation of an FFI (Foreign Function Interface). It can be used to call functions in other languages or to create an interface that allows other languages to call Rust functions.

From the book of Rust:

We also need to add a #[no_mangle] annotation to tell the Rust compiler not to mangle the name of this function. Mangling is when a compiler changes the name we’ve given a function to a different name that contains more information for other parts of the compilation process to consume but is less human readable. Every programming language compiler mangles names slightly differently, so for a Rust function to be nameable by other languages, we must disable the Rust compiler’s name mangling.

The function argument is specified as c_string_ptr: *const c_char. The *const is a raw pointer and the c_char is the C char. So combined, it means we have a pointer to a c_char.

In order to dereference the raw pointer, we start an unsafe block. Inside the block, we use CStr::from_ptr which ‘will wrap the provided ptr with a CStr wrapper’. After this, we call to_bytes() to convert the C string to a byte slice. This is all stored in ‘bytes’ variables.

We pass the byteslice to str::from_utf8() and unwrap the result, leaving us with a &str. Then we print it out.

With everything in place, we run cargo build --release. We now have the following files:

rust_lib/ ├── target/ | ├── lib.rs ├── target/ │ ├── release/ │ ├── librust_lib.so ├── print_string.py

From the rust_lib directory, we do the following:

root@rust:/python/rust/rust_lib# ./print_string.py Python says hi inside Rust!

We managed to call a Rust function from Python and print a value to console.

Calling a Rust function from Python to print a number to screen.

When passing arguments from Python to Rust, we need to think about the type that is used in Python, C and Rust. Let’s print an integer to screen. First, we create the Python script:

import ctypes

rust_lib = ctypes.CDLL("target/release/librust_lib.so")

if __name__ == "__main__":

SOME_BYTES = (2).to_bytes(4, byteorder="little")

rust_lib.print_int(SOME_BYTES)

Next, we move over to the Rust side and add the following to our lib.rs:

use std::os::raw::c_int;

// Turn a C-int into a &i32 and print to console:

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn print_int(c_int_ptr: *const c_int) {

let int_ptr = unsafe { c_int_ptr.as_ref().unwrap() };

println!("Python gave us number {}", int_ptr);

}

We brought another type into scope, this time the c_int. The function takes a pointer to a C integer as an argument. After we cargo build --release again, we can run the Python script:

root@rust:/python/rust/rust_lib# python3 print_number.py Python gave us number 2

There are many types in Rust, Python and C. This can get confusing!

Calling a Rust function from Python with multiple types

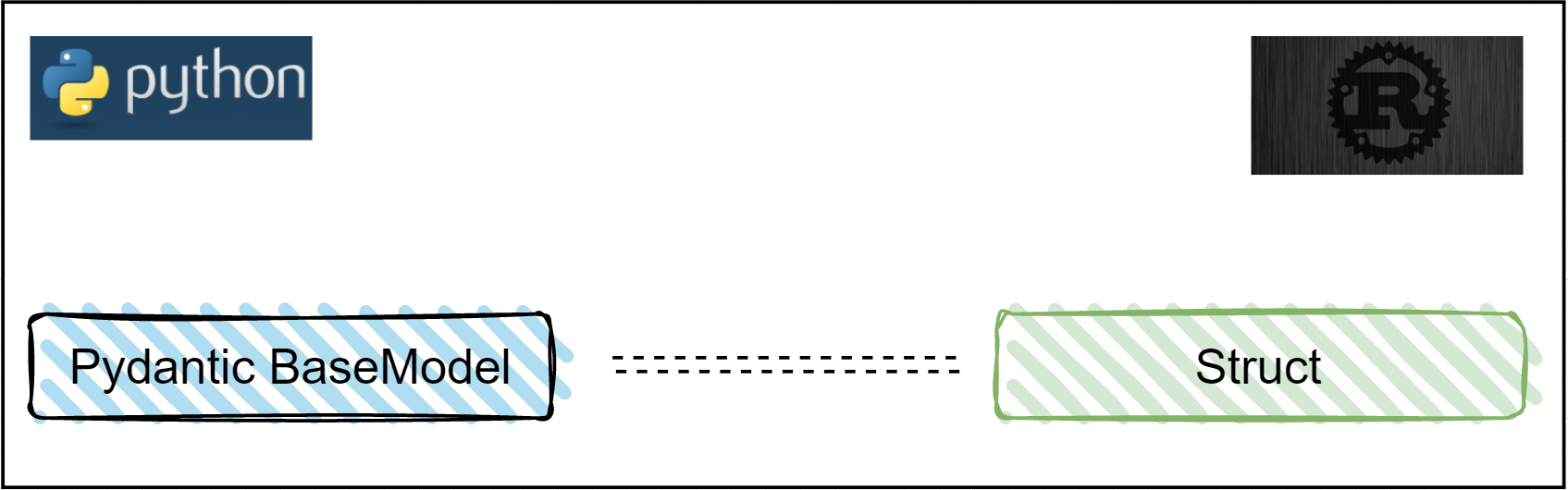

This time, Python will call a Rust function called start_procedure. To avoid distractions, it does not do anything other then taking a struct and returning another one. On the Python side, we use a Pydantic basemodel to create the input that the Rust function requires. The Pydantic basemodel will have the same fields as the Rust struct. We do the same thing for the return value from Rust. We create a Pydantic basemodel that mirrors the Rust struct on the Python side. The struct and Pydantic basemodel will contain fields of multiple different types. This is something we will be dealing with in the (according to me at least) easiest way possible: by using the C Char *.

The picture illustrates what will happen. Between Rust and Python, JSON strings are used to communicate the values. In Rust, we marshal the JSON into the corresponding struct. And on the Python side, we load the JSON into the corresponding Pydantic basemodel. The advantage is that we only have to work with Char * in C and we do not have to work with C structs or any other type in C.

The Python side.

The Python script we will use is the following:

import ctypes

from pydantic import BaseModel

from typing import List

rust = ctypes.CDLL("target/release/librust_lib2.so")

class ProcedureInput(BaseModel):

timeout: int

retries: int

host_list: List[str]

action: str

job_id: int

class ProcedureOutput(BaseModel):

job_id: int

result: str

message: str

failed_hosts: List[str]

if __name__ == "__main__":

procedure_input = ProcedureInput(

timeout=10,

retries=3,

action="reboot",

host_list=["server1", "server2"],

job_id=1,

)

ptr = rust.start_procedure(procedure_input.json().encode("utf-8"))

returned_bytes = ctypes.c_char_p(ptr).value

procedure_output = ProcedureOutput.parse_raw(returned_bytes)

print(procedure_output.json(indent=2))

We start of loading the library. After that, we define 2 classes. The two classes are Pydantic basemodels, which enforces type hints at runtime. The ProcedureInput is the argument to the Rust function and the ProcedureOutput is what we expect to get in return from the Rust function.

After defining the classes, we instantiate an instance of ProcedureInput. Using rust.start_procedure, we call the Rust function. When calling the Rust function, the expression procedure_input.json().encode("utf-8") will output the fields of the class instance as a JSON string and convert that string to bytes.

We collect the return from Rust in ptr. Next, this is converted to bytes and the parse_raw method will enable us to build the ProcedureOutput instance from these bytes.

When we run the Python code, we get the following output:

root@rust:/python/rust/rust_lib# python3 call_rust_function.py

{

"job_id": 1,

"result": "success",

"message": "1 host failed",

"failed_hosts": [

"server1"

]

}

The Rust side.

The following is the code that was put in place on the Rust side:

extern crate serde;

extern crate serde_json;

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

use std::ffi::CStr;

use std::ffi::CString;

use std::os::raw::c_char;

use std::str;

#[derive(Debug, Serialize, Deserialize)]

struct ProcedureInput {

timeout: u8,

retries: u8,

host_list: Vec<String>,

action: String,

job_id: i32,

}

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize)]

struct ProcedureOutput {

result: String,

message: String,

failed_hosts: Vec<String>,

job_id: i32,

}

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn start_procedure(c_string_ptr: *const c_char) -> *mut c_char {

let bytes = unsafe { CStr::from_ptr(c_string_ptr).to_bytes() };

let string = str::from_utf8(bytes).unwrap();

let model: ProcedureInput = serde_json::from_str(string).unwrap();

let result = long_running_task(model);

let result_json = serde_json::to_string(&result).unwrap();

let c_string = CString::new(result_json).unwrap();

c_string.into_raw()

}

fn long_running_task(model: ProcedureInput) -> ProcedureOutput {

let result = ProcedureOutput {

result: "success".to_string(),

message: "1 host failed".to_string(),

failed_hosts: vec!["server1".to_string()],

job_id: model.job_id,

};

return result;

}

Few things happening here. First, we have the structs that are ‘mirroring’ the Pydantic basemodels:

#[derive(Debug, Serialize, Deserialize)]

struct ProcedureInput {

timeout: u8,

retries: u8,

host_list: Vec<String>,

action: String,

job_id: i32,

}

#[derive(Serialize, Deserialize)]

struct ProcedureOutput {

result: String,

message: String,

failed_hosts: Vec<String>,

job_id: i32,

}

After this, we have the start_procedure function:

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn start_procedure(c_string_ptr: *const c_char) -> *mut c_char {

let bytes = unsafe { CStr::from_ptr(c_string_ptr).to_bytes() };

let string = str::from_utf8(bytes).unwrap();

let model: ProcedureInput = serde_json::from_str(string).unwrap();

let result = long_running_task(model);

let result_json = serde_json::to_string(&result).unwrap();

let c_string = CString::new(result_json).unwrap();

c_string.into_raw()

}

Same as earlier, we start of building a string from the raw pointer. After we have the string, which is the JSON we got from Python, we marshal that into the ProcedureInput struct. We pass that struct to the long_running_task which gives us a ProcedureOutput as a result. Using serde_json::to_string, we transform that struct into a JSON string in the variable result_json. From that value, we create a new C-compatible string from a container of bytes using CString::new. The struct that is returned has the into_raw() method, which consumes the CString and transfers ownership of the string to a C caller. The into_raw() method returns a pointer which we used to read the return value earlier on the Python side.

Calling a Rust function from Python with a memory leak

If we put the start_procedure on a while loop, and let it run for a while, we can see that the process will gradually start to consume more and more memory. The problem is that the value that is returned from Rust is not cleaned up.

With the following change to the Python script, we run the start_procedure call indefinitely:

while True:

ptr = rust.start_procedure(procedure_input.json().encode("utf-8"))

returned_bytes = ctypes.c_char_p(ptr).value

procedure_output = ProcedureOutput.parse_raw(returned_bytes)

print(procedure_output.json(indent=2))

If we call the script now, we can see the memory usage of the Python script slowly increase.

fixing the memory leak

To address this memory leak, we first need to create a function in Rust that cleans up the memory:

#[no_mangle]

pub extern "C" fn free_mem(c_string_ptr: *mut c_char) {

unsafe { CString::from_raw(c_string_ptr) };

}

This function will use from_raw to take ownership of a CString that was transferred to C. When the function ends, there is no more owner and the value is dropped, releasing the memory.

We need to call this function on the Python side. The input to the free_mem function should be the value that Rust returned to Python.

. We need to call this function on the Python side.

The following Python can run continuously without leaking any memory:

while True:

ptr = rust.start_procedure(procedure_input.json().encode("utf-8"))

returned_bytes = ctypes.c_char_p(ptr).value

procedure_output = ProcedureOutput.parse_raw(returned_bytes)

print(procedure_output)

rust.free_mem(ptr)

The value that is returned by start_procedure is the value we pass to free_mem. Another thing to notice is we call free_mem after we are done with the value.

In the following example, we free the value before we are done with it in the Python code:

ptr = rust.start_procedure(procedure_input.json().encode("utf-8"))

returned_bytes = ctypes.c_char_p(ptr).value

rust.free_mem(ptr)

procedure_output = ProcedureOutput.parse_raw(returned_bytes)

After havng Rust free the memory, we attempt to read the same bytes on the Python side. When we run this code, we make a double free:

root@rust:/python/rust/rust_lib# python3 call_rust_continuously_free_mem.py job_id=1 result='success' message='1 host failed' failed_hosts=['server1'] free(): double free detected in tcache 2 Aborted

Closing thoughts

Using Rust from Python was something I wanted to try out for some time now. Even thought I have been studying Rust for a while, completely moving over to Rust made no sense to any of the projects I am involved in right now. In some cases the libraries I am using are not available in Rust and in other cases the projects I am working are too big to rewrite in Rust. Also, there is the fact that I am still learning Rust.

Calling Rust from Python like this paves the way for me to:

- incorporate Rust in existing Python projects and start small

- feel more confident about existing Python projects, knowing that if speed really becomes an issue, I can give things a boost with Rust

- play around with both Python as well as Rust at the same time!

There are plenty of efforts where people use Rust to speed up Python. In many cases, you’ll also see those projects make use of pyo3. This library offers ‘Rust bindings for Python, including tools for creating native Python extension modules’. One example where this is being used is polars.

The examples from this post can be found here.

Note: when creating this post, I used CPython 3.9.2, Pydantic version 1.8.2 and Rust 1.56.0.