A thorough understanding of the Option enum and the Result enum are essential to understanding optional values and error handling in Rust. In this ariticle, I will work my way through both of them.

Introduction

To understand the Option and the Result, it is important to understand the following:

- the enum in Rust

- matching enum variants

- the Rust prelude

The enum in Rust

There are good reasons for using enums. Among others, they are good for safe input handling and adding context to types by giving a collection of variants a name. In Rust, the Option as well as the Result are enumerations, also referred to as enums. The enum in Rust is quite flexible. It can contain many data types like tuples, structs and more. Additionally, you can also implement methods on enums.

The Option and the Result are pretty straightforward though. Let’s first look at an example enum:

enum Example {

This,

That,

}

let this = Example::This;

let that = Example::That;

In the above, we define an enum called Example. This enum has 2 variants called This and That. Next, we create 2 instances of the enum, variables this and that. Both are created with their own variant. It is important to note that an instance of an enum is always 1 of the variants. When you use a field struct, you can define struct with all it’s possible fields. An enum is different because you assign only one of the variants.

Displaying the enum variants

By default, the enum variants is not something you can print to screen. Let’s bring strum_macros into scope. This makes it easy to derive ‘Display’ on the enum we defined, which we do using #[derive(Display)] above the enum definition:

use strum_macros::Display;

#[derive(Display)]

enum Example {

This,

That,

}

let this = Example::This;

let that = Example::That;

println!("Example::This contains: {}", this);

println!("Example::That contains: {}", that);

Now, we can use print to display the enum variant values to screen:

Example::This contains: This Example::That contains: That

Matching enum variants

Using the match keyword, we can do pattern matching on enums. The following function takes the Example enum as an argument:

fn matcher(x: Example) {

match x {

Example::This => println!("We got This."),

Example::That => println!("We got That."),

}

}

We can pass the matcher function a value of the Example enum. The match inside the function will determine what is printed to screen:

matcher(Example::This);

matcher(Example::That);

Running the above will print the following:

We got This. We got That

The Rust prelude

The Rust prelude, described here, is something that is a part of every program. It is a list of things that are automatically imported into every Rust program. Most of the items in the prelude are traits that are used very often. But in addition to this, we also find the following 2 items:

- std::option::Option::{self, Some, None}

- std::result::Result::{self, Ok, Err}

The first one is the Option enum, described as ‘a type which expresses the presence or absence of a value’. The later is the Result enum, described as ‘a type for functions that may succeed or fail.’

Because these types are so commonly used, their variants are also exported. Let’s go over both types in more detail.

The Option

Brought into scope by the prelude, the Option is available to us without having to lift a finger. The option is defined as follows:

pub enum Option<T> {

None,

Some(T),

}

The above tells us Option<T> is an enum with 2 variants: None and Some(T). In terms of how it is used, the None can be thought of as ‘nothing’ and the Some(T) can be thought of as ‘something’. A key thing that is not immediately obvious to those starting out with Rust is the <T>-thing. The <T> tells us the Option Enum is a generic Enum.

The Option is generic over type T.

The enum is ‘generic over type T’. The ‘T’ could have been any letter, just that ‘T’ is used as a convention where 1 generic is involved.

So what does it mean when we say ‘the enum is generic over type T’? It means that we can use it for any type. As soon as we start working with the Enum, we can (and must actually) replace ‘T’ with a concrete type. This can be any type, as illustrated by the following:

let a_str: Option<&str> = Some("a str");

let a_string: Option<String> = Some(String::from("a String"));

let a_float: Option<f64> = Some(1.1);

let a_vec: Option<Vec<i32>> = Some(vec![0, 1, 2, 3]);

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Person {

name: String,

age: i32,

}

let marie = Person {

name: String::from("Marie"),

age: 2,

};

let a_person: Option<Person> = Some(marie);

let maybe_someone: Option<Person> = None;

println!(

"{:?}\n{:?}\n{:?}\n{:?}\n{:?}\n{:?}",

a_str, a_string, a_float, a_vec, a_person, maybe_someone

);

The above code outputs the following:

Some("a str")

Some("a String")

Some(1.1)

Some([0, 1, 2, 3])

Some(Person { name: "Marie", age: 2 })

None

The code shows us the enum can be generic over standard as well as over custom types. Additionally, when we define an enum as being of type x, it can still contain the variant ‘None’. So the Option is a way of saying the following:

This can be of a type T value, which can be anything really, or it can be nothing.

Matching on the Option

Since Rust does not use exceptions or null values, you will see the Option (and as we will learn later on the Result) used all over the place.

Since the Option is an enum, we can use pattern matching to handle each variant in it’s own way:

let something: Option<&str> = Some("a String"); // Some("a String")

let nothing: Option<&str> = None; // None

match something {

Some(text) => println!("We go something: {}", text),

None => println!("We got nothing."),

}

match nothing {

Some(something_else) => println!("We go something: {}", something_else),

None => println!("We got nothing"),

}

The above will output the following:

We go something: a String We got nothing

Unwrapping the Option

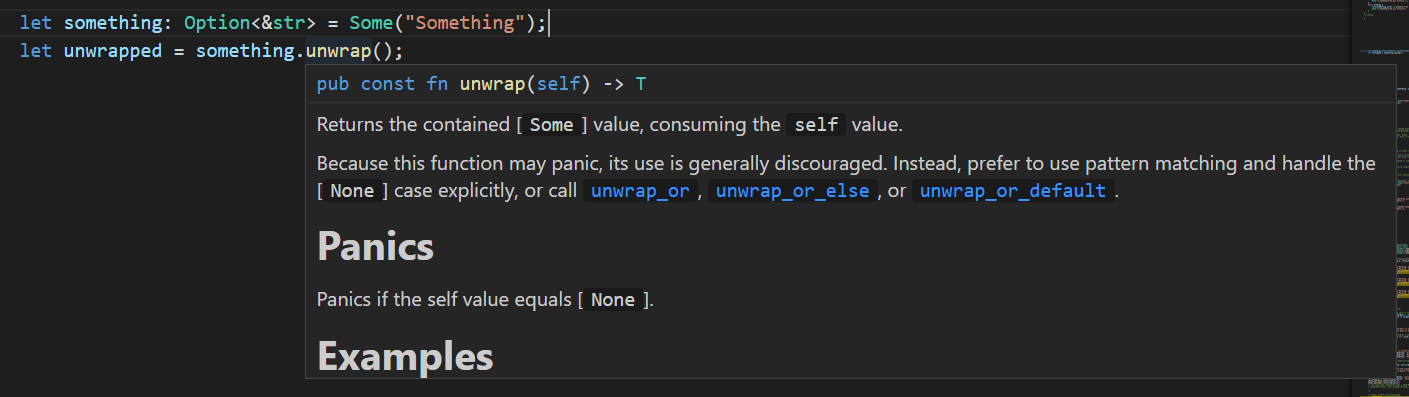

Oftentimes, you’ll see unwrap being used. This looked a bit mysterious at first. Hoovering over it in the IDE offers some clues:

In case you are using VScode, something that is nice to know is that simultaneously pressing Ctrl + left mouse button can take you to the source code. In this case, it takes us to the place in option.rs where unwrap is defined:

pub const fn unwrap(self) -> T {

match self {

Some(val) => val,

None => panic!("called `Option::unwrap()` on a `None` value"),

}

}

In option.rs, we can see unwrap is defined in the impl<T> Option<T> block. When we call it on a value, it will try to ‘unwrap’ the value that is tucked into the Some variant. It matches on ‘self’ and if the Some variant is present, ‘val’ is ‘unwrapped’ and returned. If the ‘None’ variant is present, the panic macro is called:

let something: Option<&str> = Some("Something");

let unwrapped = something.unwrap();

println!("{:?}\n{:?}", something, unwrapped);

let nothing: Option<&str> = None;

nothing.unwrap();

The code above will result in the following:

Some("Something")

"Something"

thread 'main' panicked at 'called `Option::unwrap()` on a `None` value', src\main.rs:86:17

Calling unwrap on an Option is quick and easy but letting your program panic and crash is not a very elegant or safe approach.

Option examples

Let’s look at some examples where you could use an Option.

Passing an optional value to a function

fn might_print(option: Option<&str>) {

match option {

Some(text) => println!("The argument contains the following value: '{}'", text),

None => println!("The argument contains None."),

}

}

let something: Option<&str> = Some("some str");

let nothing: Option<&str> = None;

might_print(something);

might_print(nothing);

This outputs the following:

The argument contains the following value: 'some str' The argument contains None.

Having a function return an optional value

// Returns the text if it contains target character, None otherwise:

fn contains_char(text: &str, target_c: char) -> Option<&str> {

if text.chars().any(|ch| ch == target_c) {

return Some(text);

} else {

return None;

}

}

let a = contains_char("Rust in action", 'a');

let q = contains_char("Rust in action", 'q');

println!("{:?}", a);

println!("{:?}", q);

We can safely assign the return of this function to a variable and, later on, use match to determine how to handle a ‘None’ return. The previous code prints the following:

Some("Rust in action")

None

Let’s examine three different ways to work with the Optional return.

The first one, which is the least safe, would be simply calling unwrap:

let a = contains_char("Rust in action", 'a');

let a_unwrapped = a.unwrap();

println!("{:?}", a_unwrapped);

The second, safer option, is to use a match statement:

let a = contains_char("Rust in action", 'a');

match a {

Some(a) => println!("contains_char returned something: {:?}!", a),

None => println!("contains_char did not return something, so branch off here"),

}

The third option is to capture the return of the function in a variable and use if let:

let a = contains_char("Rust in action", 'a');

if let Some(a) = contains_char("Rust in action", 'a') {

println!("contains_char returned something: {:?}!", a);

} else {

println!("contains_char did not return something, so branch off here")

}

Optional values inside a struct

We can also use the Option inside a struct. This might be useful in case a field may or may not have any value:

#[derive(Debug)]

struct Person {

name: String,

age: Option<i32>,

}

let marie = Person {

name: String::from("Marie"),

age: Some(2),

};

let jan = Person {

name: String::from("Jan"),

age: None,

};

println!("{:?}\n{:?}", marie, jan);

The above code outputs the following:

Person { name: "Marie", age: Some(2) }

Person { name: "Jan", age: None }

Real world example

An example where the Option is used inside Rust is the pop method for vectors. This method returns an Option<T>. The pop-method returns the last element. But it can be that a vector is empty. In that case, it should return None. An additional problem is that a vector can contain any type. In that case, it is convenient for it to return Some(T). So for that reason, pop() returns Option<T>.

The pop method for the vec from Rust 1.53:

impl<T, A: Allocator> Vec<T, A> {

// .. lots of other code

pub fn pop(&mut self) -> Option<T> {

if self.len == 0 {

None

} else {

unsafe {

self.len -= 1;

Some(ptr::read(self.as_ptr().add(self.len())))

}

}

}

// lots of other code

}

A trivial example where we output the result of popping a vector beyond the point where it is still containing items:

let mut vec = vec![0, 1];

let a = vec.pop();

let b = vec.pop();

let c = vec.pop();

println!("{:?}\n{:?}\n{:?}\n", a, b, c);

The above outputs the following:

Some(1) Some(0) None

The result

Another important construct in Rust is the Result enum. Same as with the Option, the Result is an enum. The definition of the Result can be found in result.rs:

pub enum Result<T, E> {

/// Contains the success value

Ok(T),

/// Contains the error value

Err(E),

}

The Result enum is generic over 2 types, given the name T and E. The T is used for the OK variant, which is used to express a successful result. The E is used for the Err variant, used to express an error value. The fact that Result is generic over E makes it possible to communicate different errors. If Result would not have been generic over E, there would just be 1 type of error. Same as there is 1 type of ‘None’ in Option. This would not leave a lot of room when using the error value in our flow control or reporting.

As indicated before, the Prelude brings the Result enum as well as the Ok and Err variants into scope in the Prelude like so:

std::result::Result::{self, Ok, Err}

This means we can access Result, Ok and Err directly at any place in our code.

Matching on the Result

Let’s start off creating an example function that returns a Result. In the example function, we check whether a string contains a minimum number of characters. The function is the following:

fn check_length(s: &str, min: usize) -> Result<&str, String> {

if s.chars().count() >= min {

return Ok(s)

} else {

return Err(format!("'{}' is not long enough!", s))

}

}

It is not a very useful function, but simple enough to illustrate returning a Result. The function takes in a string literal and checks the number of characters it contains. If the number of characters is equal to, or more then ‘min’, the string is returned. If this is not the case, an error is returned. The return is annotated with the Result enum. We specify the types that the Result will contain when the function returns. If the string is long enough, we return a string literal. If there is an error, we will return a message that is a String. This explains the Result<&str, String>.

The if s.chars().count() >= min does the check for us. In case it evaluates to true, it will return the string wrapped in the Ok variant of the Result enum. The reason we can simply write Ok(s) is because the variants that make up Result are brought into scope as well. We can see that the else statement will return an Err variant. In this case, it is a String that contains a message.

Let’s run the function and output the Result using dbg!:

let a = check_length("some str", 5);

let b = check_length("another str", 300);

dbg!(a); // Ok("some str",)

dbg!(b); // Err("'another str' is not long enough!",)

We can use a match expression to deal with the Result that our function returns:

let func_return = check_length("some string literal", 100);

let a_str = match func_return {

Ok(a_str) => a_str,

Err(error) => panic!("Problem running 'check_length':\n {:?}", error),

};

// thread 'main' panicked at 'Problem running 'check_length':

// "'some string literal' is not long enough!"'

Unwrapping the Result

Instead of using a match expression, there is also a shortcut that you’ll come across very often. This shortcut is the unwrap method that is defined for the Result enum. The method is defined as follows:

impl<T, E: fmt::Debug> Result<T, E> {

...

pub fn unwrap(self) -> T {

match self {

Ok(t) => t,

Err(e) => unwrap_failed("called `Result::unwrap()` on an `Err` value", &e),

}

}

...

}

Calling unwrap returned the contained ‘Ok’ value. If there is no ‘Ok’ value, unwrap will panic. In the following example, the from_str method returns an ‘Ok’ value:

use serde_json::json;

let json_string = r#"

{

"key": "value",

"another key": "another value",

"key to a list" : [1 ,2]

}"#;

let json_serialized: serde_json::Value = serde_json::from_str(&json_string).unwrap();

println!("{:?}", &json_serialized);

// Object({"another key": String("another value"), "key": String("value"), "key to a list": Array([Number(1), Number(2)])})

We can see that ‘json_serialized’ contains the value that was wrapped in the ‘Ok’ variant.

The following demonstrates what happened when we call unwrap on a function that does not return an ‘Ok’ variant. Here, we call ‘serde_json::from_str’ on invalide JSON:

use serde_json::json;

let invalid_json = r#"

{

"key": "v

}"#;

let json_serialized: serde_json::Value = serde_json::from_str(&invalid_json).unwrap();

/*

thread 'main' panicked at 'called `Result::unwrap()` on an `Err` value: Error("control character (\\u0000-\\u001F) found while parsing a string", line: 4, column: 0)',

*/

There is a panic and the program comes to a halt. Instead of unwrap, we could also choose to use expect.

use serde_json::json;

let invalid_json = r#"

{

"key": "v

}"#;

let b: serde_json::Value =

serde_json::from_str(&invalid_json).expect("unable to deserialize JSON");

This time, when we run the code, we can also see the message that we added to it:

thread 'main' panicked at 'unable to deserialize JSON: Error("control character (\\u0000-\\u001F) found while parsing a string", line: 4, column: 0)'

Since unwrap and expect result in a panic, it ends the program, period. Most oftentimes, you’ll see unwrap being used in the example section, where the focus is on the example and lack of context really prohibits proper error handling for a specific scenario. The example section, code comments and documentation examples is where you will most oftentimes encounter unwrap. See for instance the example to have serde serialize fields as camelCase:

use serde::Serialize;

#[derive(Serialize)]

#[serde(rename_all = "camelCase")]

struct Person {

first_name: String,

last_name: String,

}

fn main() {

let person = Person {

first_name: "Graydon".to_string(),

last_name: "Hoare".to_string(),

};

let json = serde_json::to_string_pretty(&person).unwrap(); // <- unwrap

// Prints:

//

// {

// "firstName": "Graydon",

// "lastName": "Hoare"

// }

println!("{}", json);

}

Example taken from the serde documentation, right here.

Using ? and handling different errors

Different projects oftentimes define their own errors. Searching a repo for something like pub struct Error or pub enum Error can sometimes reveal the errors defined for a project. But the thing is, different crates and projects might return their own error type. If you have a function that uses methods from a variety of projects, and you want to propagate that error, things can get a bit trickier. There are several ways to deal with this. Let’s look at an example where we deal with this by ‘Boxing’ the error.

In the next example, we define a function that reads the entire contents of target file into a string and then serializes it into JSON, while mapping it to a struct. The function returns a Result. The Ok variant is the ‘Person’ struct and the Error that will be propagated can be an error coming serde or std::fs. To be able to return errors from both these packages, we return Result<Person, Box<dyn Error>>. The ‘Person’ is the Ok variant of the Result. The Err variant is defined as Box<dyn Error>, which represents ‘any type of error’.

Another thing worth mentioning about the following example is the use of ?. We will use fs::read_to_string(s) to read a file as a string and we will use erde_json::from_str(&text) to serialize the text to a struct. In order to avoid having to write match arms for the Results returned by those methods, we place the ? behind the call to those methods. This syntactic sugar will perform an unwrap in case the preceding Result contains an Ok. If the preceding Result contains an Err variant, it ensures that this Err is returned just as if the return keyword would have been used to propagate the error. And when the error is returned, our ‘Box’ will catch them.

The example code:

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

use std::error::Error;

use std::fs;

// Debug allows us to print the struct.

// Deserialize and Serialize adds decoder and encoder capabilities to the struct.

#[derive(Debug, Deserialize, Serialize)]

struct Person {

name: String,

age: usize,

}

fn file_to_json(s: &str) -> Result<Person, Box<dyn Error>> {

let text = fs::read_to_string(s)?;

let marie: Person = serde_json::from_str(&text)?;

Ok(marie)

}

let x = file_to_json("json.txt");

let y = file_to_json("invalid_json.txt");

let z = file_to_json("non_existing_file.txt");

dbg!(x);

dbg!(y);

dbg!(z);

The first time we call the function, it succeeds and dbg!(x); outputs the following:

[src\main.rs:20] x = Ok(

Person {

name: "Marie",

age: 2,

},

)

The second calls encounters an error. The file contains the following:

{

"name": "Marie",

"a

}

This file can be opened and read to a String, but Serde cannot parse it as JSON. This function call outputs the following:

[src\main.rs:21] y = Err(

Error("control character (\\u0000-\\u001F) found while parsing a string", line: 3, column: 4),

)

We can see the Serde error was properly propagated.

The last function call tried to open a file that does not exist:

[src\main.rs:22] z = Err(

Os {

code: 2,

kind: NotFound,

message: "The system cannot find the file specified.",

},

)

That error, coming from std::fs, was also properly propagated.

using other crates: anyhow

There are many crates available to help us deal with errors. Some help us manage boilerplate code, others add features such as extra reporting. One example of a crate that is easy to use when starting out with Rust is anyhow:

This crate will give us a simplified Result type and we can easily annotate our errors by adding context. The following code snippet illustrates the three basic things that anyhow equips us with:

use anyhow::{anyhow, Context, Result};

use serde::{Deserialize, Serialize};

use std::fs;

#[derive(Debug, Deserialize, Serialize)]

struct Secrets {

username: String,

password: String,

}

fn get_secrets(s: &str) -> Result<Secrets> {

let text = fs::read_to_string(s).context("Secrets file is missing.")?;

let secrets: Secrets =

serde_json::from_str(&text).context("Problem serializing secrets.")?;

if secrets.password.chars().count() < 2 {

return Err(anyhow!("Password in secrets file is too short"));

}

Ok(secrets)

}

In the above example, anyhow = "1.0.43" was added to the Cargo.toml file. At the top, three things are brought into scope. These are anyhow, Context and Result. Let’s discuss them one by one.

anyhow::Result

A (more) convenient type to work with and deal with errors. You can also use this on main(). The get_secrets function is where we see this Result in use. It is this enum for which traits have been implemented that make things easier. One of those traits, that we will discuss next, is called ‘Context’.

If we run get_secrets and all is well, we get the following return:

let a = get_secrets("secrets.json");

dbg!(a);

The above will output the following:

/*

[src\main.rs:] a = Ok(

Secrets {

username: "username",

password: "password",

},

)

*/

We got a ‘normal’ Ok value.

anyhow::Context

As errors are propagated, the Context trait allows you to wrap the original error and include a message for more contextual awareness. Previously, we would open a file like so:

let text = fs::read_to_string(s)?;

This will open the file and unwrap the Ok variant. Alternatively, if read_to_string returns an Err, the ? will propagate that error. Now, we have the following:

let text = fs::read_to_string(s).context("Secrets file is missing.")?;

We did something similar with for the serde_json::from_str method. We can use the following to trigger 2 errors:

let b = get_secrets("secrets.jsonnn");

dbg!(b);

let c = get_secrets("invalid_json.txt");

dbg!(c);

In the first case, there will be an error because the file does not exist. In the second case, Serde will give us an error because it cannot parse the JSON. The above functions output the following:

[src\main.rs:358] b = Err(

Error {

context: "Secrets file is missing.",

source: Os {

code: 2,

kind: NotFound,

message: "The system cannot find the file specified.",

},

},

)

[src\main.rs:361] c = Err(

Error {

context: "Problem serializing secrets.",

source: Error("control character (\\u0000-\\u001F) found while parsing a string", line: 3, column: 4),

},

)

anyhow::anyhow

This is a macro that you can use to have a function return an anyhow::Error. The following loads some JSON that contains a password that is too short (silly example I know):

let d = get_secrets("wrong_secrets.json");

dbg!(d);

The result would be the following:

[src\main.rs:364] d = Err(

"Password in secrets file is too short",

)

The anyhow crate was forked by Jane Lusby. She created eyre. That is also something worth checking out. Especially combined with the excellent Rustconf 2020 talk, dubbed Error handling Isn’t All About Errors.

Wrapping up

Understanding how the Option as well as the Result is used in Rust is very important. The above explanation of the Option, Result and error handling in Rust is my written account of how I learned about them. I hope this article will benefit others.

The code used in this article can be found here. In addition to that, here are some additional links that are worth checking out to better understand the Option, the Result and error handling in Rust:

- The Rust Programming Language Chapter 6 and Chapter 9

- From Rustconf 2020 talks, the Error handling Isn’t All About Errors talk by by Jane Lusby

- Error handling and dealing with multiple error types in Rust by example

- Next level thoughts and ideas on errors

- Wrapping errors