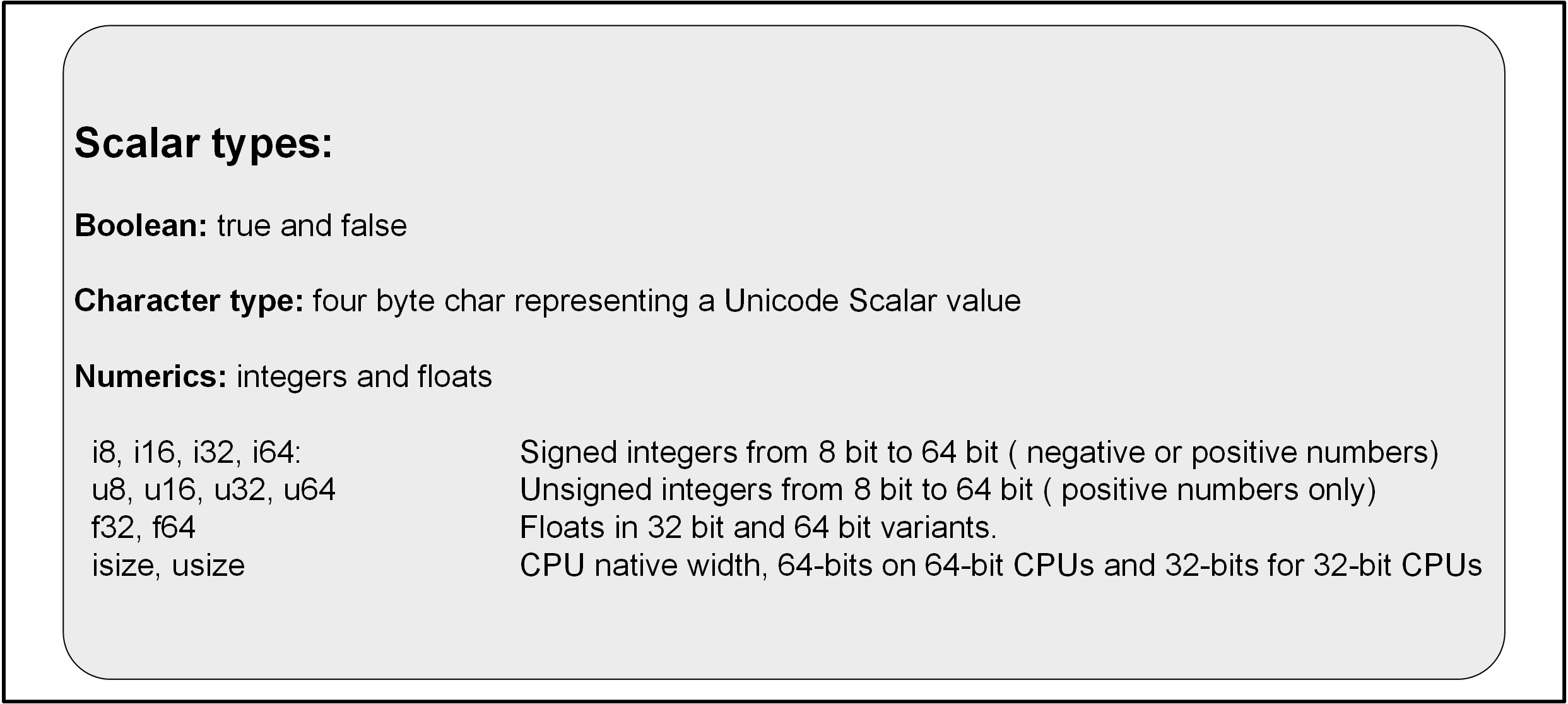

Scalar types

Scalar types are types representing a single value. In Rust, we can identify the following scalar types:

Creating and printing these values in a program can be done as follows:

fn main() {

let ch: char = 'z'; // four bytes, expresses single Unicode Scalar Value

let b: bool = true; // true or false

let i: i32 = -111; // 32 bit signed integer, can be positive or negative

let f: f32 = 3.4; // 32 bit float number

println!("char: {}\nbool: {}\ni32: {}\nfloat32: {}\n", ch, b, i, f);

}

When we cargo run the above, we get the following output:

char: z bool: true i32: -111 float32: 3.4

To be able to run the example without having Rust installed, go here.

The let keyword was used the bind a value to a variable. In the previous example, we explicitly specified a type for every variable. In a lot of cases, the Rust compiler can also infer the type. The following would also work:

fn main() {

let ch = 'z';

let b = true;

let i = -111;

let f = 3.4;

println!("char: {}\nbool: {}\ni32: {}\nfloat32: {}\n", ch, b, i, f);

}

The above is valid, though it is not the same as the first code snippet. When the compiler has to infer the type, it settles on using i32 for the integer variable and f64 for the float variable.

Another thing worth pointing out is that variables are immutable by default. In the following code, we try to change the value of b from true to false:

fn main() {

let b = true;

println!("b contains: {}", b);

b = false;

println!("b now contains: {}", b);

}

When we run the above, we get the following:

error[E0384]: cannot assign twice to immutable variable `b` --> src\main.rs:3:5 | 2 | let b = true; | - | | | first assignment to `b` | help: consider making this binding mutable: `mut b` 3 | b = false; | ^^^^^^^^^ cannot assign twice to immutable variable

Even though the compiler does not let us run the code, it is nice enough to give us a hint:

help: consider making this binding mutable: `mut b`

If we want to be able to change the value of a variable, we need to specify that a variable is mutable. This is done when we define the variable and we use the mut keyword to do so:

fn main() {

let mut b = true;

println!("b contains: {}", b);

b = false;

println!("b now contains: {}", b);

}

We can now run the code without any errors:

b contains: true b now contains: false

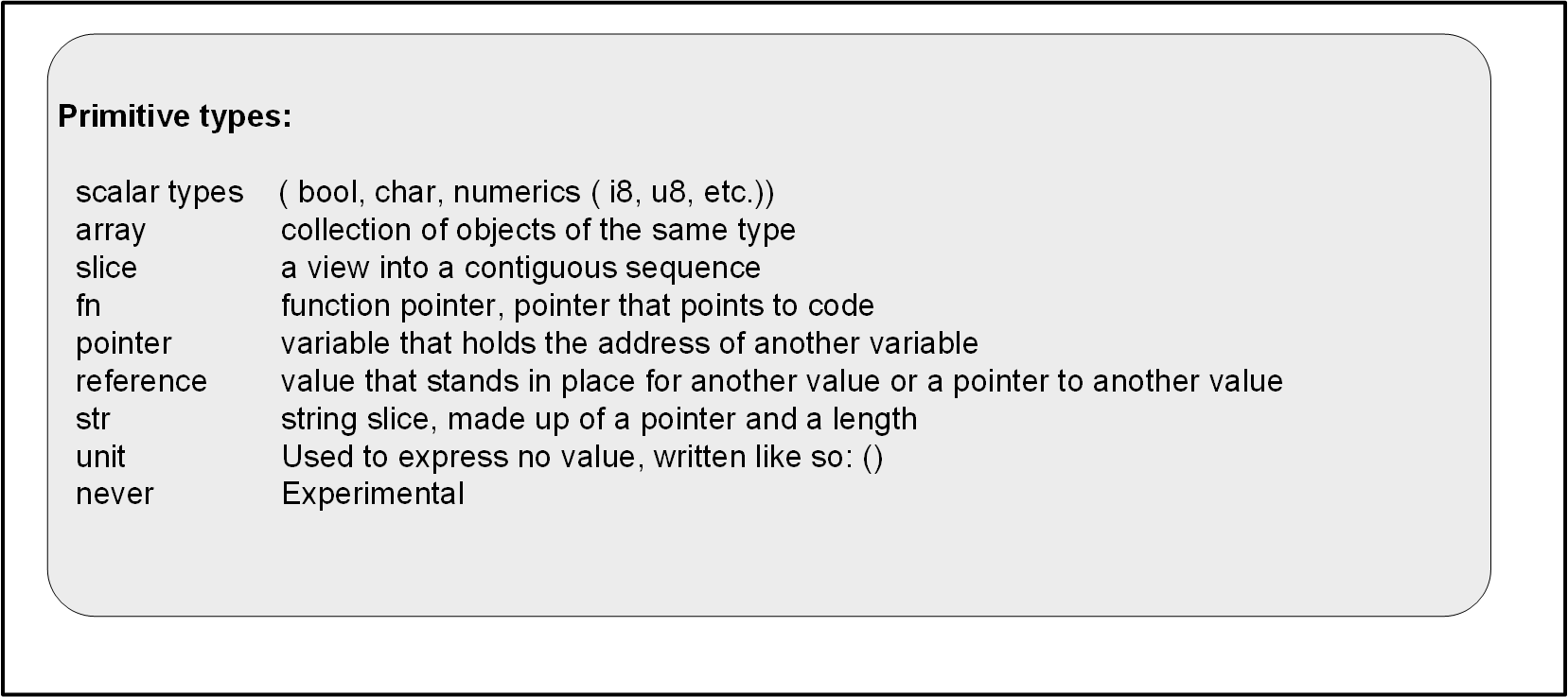

Oftentimes, you will also read about primitive types. These primitive types include the scalar types as well as some additional ones:

The language doc mentions the entire list of primitive types here. It does a good job of thoroughly explaining all the types and their behaviours. I will cover most of the primitive types in future posts. There is one last thing I want touch on in this post.

Copy semantics and move semantics

I wanted to include this right at the beginning because it was so confusing to me when I was starting out with Rust. All primitive types share a few common traits. In Rust, traits are used to define shared behaviour. One particularly interesting trait for the primitive types is the Copy trait.

Types that have the copy traits are said to have copy semantics. What this means is that when you pass them into a function, you pass a copy of that value into that function.

Non-primitive types do not have the Copy trait by default. This means they are subject to move semantics. When you pass them into a function, you move the value into that function. Without going into details (that I am still learning about myself), this pretty much means that when the function scope ends, the value is destroyed.

Here is an example function that takes in a primitive type:

fn main() {

let i: i32 = 100;

// Using primitive types in func is done using 'copy semantics':

copy_semantics(i);

// We can still use the values after the function scope closes:

println!("i32: {}", i);

}

fn copy_semantics(i: i32) {

println!("i32: {}", i);

}

In the code above, we define an i32 which we then pass to a function. Here, the Copy trait ensures that the value of i is copied into the function. After the copy_semantics function completes, i still exists and we print the variable to screen. This code will run without any errors.

The following illustrates the move semantics using a struct:

fn main() {

// All non-primitive types move-semantics by default:

let marie = Person {

name: String::from("marie"),

age: 2,

};

move_semantics(marie);

// Next line is illegal because a move happened when we passed marie to a function:

println!("{} is {} years old.", marie.name, marie.age);

}

fn move_semantics(person: Person) {

println!("{} is {} years old.", person.name, person.age);

}

struct Person {

name: String,

age: u8,

}

In the above code, we define a struct and pass it into a function. In this case, the value is moved into the function. When the function move_semantics completes, the variable is destroyed and marie is no more. Running the above code will give us the following error:

cargo run

Compiling testing v0.1.0 (example)

error[E0382]: borrow of moved value: `marie`

--> src\main.rs:9:49

|

3 | let marie = Person {

| ----- move occurs because `marie` has type `Person`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

...

7 | move_semantics(marie);

| ----- value moved here

8 | // Next line is illegal because a move happened when we passed marie to a function:

9 | println!("{} is {} years old.", marie.name, marie.age);

| ^^^^^^^^^ value borrowed here after move

error: aborting due to previous error

For more information about this error, try `rustc --explain E0382`.

error: could not compile `testing`

To learn more, run the command again with --verbose.

Here we see the compiler mention a few things. Let’s start with the following:

3 | let marie = Person {

| ----- move occurs because `marie` has type `Person`, which does not implement the `Copy` trait

The compiler points out to use the fact that the Person struct, does not implement the Copy trait. After that, it goes on to tell us where we have a move:

7 | move_semantics(marie); | ----- value moved here

Finally, it points us to where we encounter a problem:

9 | println!("{} is {} years old.", marie.name, marie.age);

| ^^^^^^^^^ value borrowed here after move

It is saying value borrowed here after move. Because the value was moved into the move_semantics function, it was destroyed after that function was completed. There are ways to deal with this, using a reference for instance. The following code would run:

fn main() {

let marie = Person {

name: String::from("marie"),

age: 2,

};

// the & before marie means we are now passing a reference.

move_semantics(&marie);

println!("{} is {} years old.", marie.name, marie.age);

}

// The '&' before Person means the functionn now takes a reference.

fn move_semantics(person: &Person) {

println!("{} is {} years old.", person.name, person.age);

}

struct Person {

name: String,

age: u8,

}

The specifics on why this works, and what other solutions we could implement here, are for a future post.

Wrapping up

As I learn more about Rust, I will dive into more complicated features of the language. My goal is to learn it proper and cover the foundations first. This first post on Rust covered covered the scalar types and some other basics, like defining variables. For more on scalars and the other primitive types, you can check the docs. Rust primitives offers pretty comprehensive examples and explanations.